Truly there exist letters from emigrants describing the voyage from home to the final destination. Unfortunately I'm not able to quote such letters, at least not letters that have been translated to English. The reason? Simply, I don't have any.

In the beginning of the Emigration period there were extensive debates in the Icelandic papers about the merits of emigration. The early emigrants wrote glowing letters about free land, abundant pasture for livestock, comparatively good wages, and boundless opportunities. The establishment of merchants, clergy, officials, and others in Iceland who depended on a large population and cheap labor for their positions tried to counter these claims. They argued that high costs matched the high wages, Icelanders were never meant to till the soil, that it would be difficult to exist where Icelandic was not spoken, that there were many perils awaiting, and that it was unpatriotic to leave the motherland. Anyway, in the end, about 15,000 people emigrated during the period from 1870 to 1914. Some estimate the emigrating number up to 20,000. The Canadian government printed posters in many languages that advertised 160 acres of free land to each settler with 200 million acres available in Western Canada. This offer may have been the most influential factor of all.

|

Granton harbour around 1880 |

In the "Records of Emigration" only 40 emigrants are recorded in the years 1870 to 1872. In 1873 the first big group left Iceland, 343 recorded and the major part was from Northern Iceland. In this group was Guðmundur Stefánsson, a farmers hand at Mýri in Bárðardalur in Thingeyjarsýsla County with his wife Guðbjörg Hannesdóttir and their daughter Sigurlaug Einara Guðmundsdóttir. Their son was Stefán Guðmundsson who emigrated at the same time from a nearby farm, Mjóidalur, where he was a farmer's hand. He accompanied the family there, Jón Jónsson, the farmer, his wife Sigurbjörg Stefánsdóttir and their two children the son Jón Jónsson, then 9 years old and the daughter Helga Sigríður Jónsdóttir, age 14, who few years later married previous mentioned Guðmundur Stefánsson, who became widely known poet, by the name Stephan G. Stephanson.

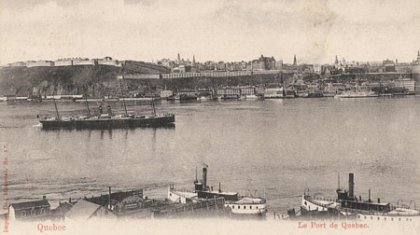

These people all boarded S.s. Queen at Akureyri and sailed to Granton in Scotland. From Granton they took a train to Glasgow from where S/S Manitoban took them to Quebec, Canada.

The following description of the train trip from Granton Harbour to the ship at Glasgow is taken from an account of Guðmundur Stefánsson and his family's voyage in 1873.

"We were left to wait there by our luggage until we were told that a steam engine had arrived to take us to Glasgow. That was the first time I saw a steam engine. It is no easy task to describe this gigantic monster, which kills everything that gets in its way. It glistens beautifully, all made of iron with a funnel poking up from it for the steam. Behind the funnel was another pipe, much narrower, with a string attached. When the string is pulled, the pipe lets out a terrifying hoot that can be heard miles away. Anyone who has not heard it before is scared out of his wits. This hoot means "look out" and if the warning is not heeded, the creature that does not obey is death's prey. Behind the engine comes the coal wagon, then the luggage cars, which are full of goods and possessions belonging to emigrants. Then come the passenger carriages, which are very long. Here I can describe their width: along the length of the carriage is a passage wide enough for one person. On both sides of it are seats, like those in churches, wide enough for two.

The carriages are about two meters high, with paneled ceilings and floors, and the finest of them are all painted and have padded seating. There are large glass windows, one after another on both sides of the carriage, so one can see everything outside and have the windows open if it is hot. There is a toilet in each carriage and a water container to drink from if one is thirsty. Then all these carriages are joined together, one after another, possibly 20 to 30 in all. It is such a long train that it seems incredible to one who has not seen it with his own eyes that the steam engine could pull this whole train along, with such power, that it only takes an hour to cover the distance a man on horseback would cover in a day. Now this would all be fine if it weren't for the danger involved.

We were then told to hurry up on board. ... The train headed for Edinburgh, where there was another long wait. We got off the train and walked around the town a little with Lambertsen (the Allan Line agent). Then we set off again and for a while we traveled underground in pitch darkness, then came out into daylight again. The view of the countryside was beautiful: attractive fields and bushes made a pretty scene that flew past as the train tore on ahead.

In a short while we were told to get off the train as we had arrived in Glasgow. The street lamps had been lit. It was a long walk to the inn where we were to stay. ... We were followed by an enormous crowd of locals. Never before have I seen so many people gathered in one place. There were all sorts of ruffians who made fun of us and generally misbehaved, sometimes trying to break up our ranks but we showed them our tempers and they backed off.

At last we reached the inn building where we were counted like sheep as we entered. Here we were fed and had a bed for the night. ...

We stayed here all day. ... I did not wander far; there are many traps, treachery and stealing. The horses here are the biggest I have ever seen. They tower over me, though you will not believe it. ... The next morning we were to go on board the ship that would transport us across the Atlantic. We had to walk almost as far as we had done the day we arrived in Glasgow. At last we reached the ship that lay beside the pier so we only had to step on board.

We were told to go below deck and make ourselves comfortable. We Icelanders were all together in one room. It was tolerable, though rather cramped. An hour later we were ordered up on deck to be counted and have our tickets examined. Then we were ordered back down again. We were 720 passengers in all. Along the sides of the ship were toilets, one side for men, the other for women; each toilet had space for seven at once, and everything fell straight down into the sea."

|

Thorsmork.

Since then I have kept in close contact with relatives in

Iceland and I have also expanded the family web in North America to

include distant cousins whose ancestors also emigrated. Many of those

went to Utah and contact was lost years and years ago. However, we now

have renewed connections that have enabled us all to fill in more pieces

of the puzzle. So, now you know how I became interested in my Icelandic

origin.

Thorsmork.

Since then I have kept in close contact with relatives in

Iceland and I have also expanded the family web in North America to

include distant cousins whose ancestors also emigrated. Many of those

went to Utah and contact was lost years and years ago. However, we now

have renewed connections that have enabled us all to fill in more pieces

of the puzzle. So, now you know how I became interested in my Icelandic

origin.

Stephan G. Stephanson (1853-1927)

Stephan G. Stephanson (1853-1927)

Guðbjörg Guðmundsdóttir (1866-1941)

Guðbjörg Guðmundsdóttir (1866-1941)